You can do the opposite of a losing strategy and still lose. That’s important to keep in mind when considering whether to take the opposite side of trades recommended by losing advisers.

Given that the vast majority of investment advisers and fund managers lag the market, doing the mirror opposite of what they’re doing seems to many a sure path to beating the market.

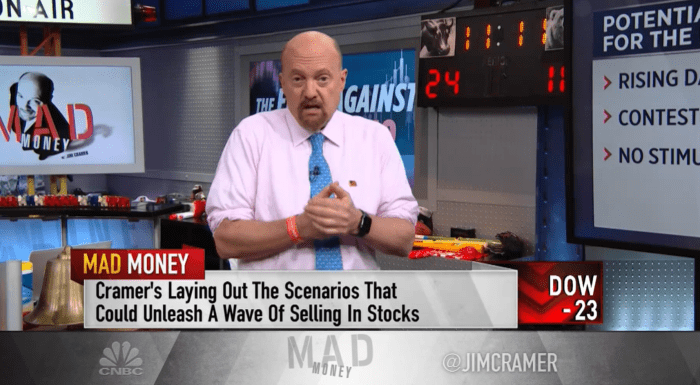

This idea is not new, as I’ve been asked about it numerous times over the four-plus decades in which my firm has audited investment newsletter returns. But in recent years the exchange-traded fund industry has gotten into the act. One of the newer of such ETFs was launched by Tuttle Capital Management in March 2023. Designed to do the opposite of what TV personality Jim Cramer recommends, this ETF is the Inverse Cramer Tracker ETF

SJIM,

Our first clue that this inverse ETF may not beat the market, even if and when Cramer’s picks are themselves market laggards, comes from its performance since inception. Tuttle Capital calculates that Cramer’s picks lost 0.5% through May 1, versus gains of 4.9% for the S&P 500

SPX,

There are several reasons why both the original and the inverse versions of a strategy would lose money:

Transaction Costs

One of the biggest factors is transaction costs. One way of thinking about their impact is to imagine a manager whose stock-picking ability is no better or worse than random. The manager’s long-term returns will be equal to that of the market as a whole, minus transaction costs — and so, also, will the return of the inverse of the recommendations.

Transaction costs are always important to keep in mind, of course, but especially for the ETFs that are inverse to other strategies, which tend to have high fees. The Inverse Cramer Tracker ETF, for example, has an expense ratio of 1.2%, much higher than the 0.16% average for all equity ETFs (according to ETF.com). By comparison, for example, AXS Short Innovation Daily ETF

SARK,

Magnitude of loss matters

Even when the inverse of a losing adviser’s strategy makes money, it can still lag the market. That will be the case, for example, when the absolute value of the adviser’s loss is less than the market.

Take the ARK Innovation ETF return since the beginning of 2020, which lost 9.0% annualized through early May in contrast to a total return of 9.7% annualized for the S&P 500 and 14.0% for the Nasdaq 100. While the SARK inverse ETF hasn’t existed over this period, assume that its performance would have been the mirror opposite of ARKK’s. In that event, though it would have made money, it also would have lagged the S&P 500.

Risk-adjusted performance

A more subtle factor that can sabotage the inverse version of a losing manager’s strategy is volatility, and specifically volatility’s impact on the inverse strategy’s risk-adjusted performance. For a risky strategy to beat the market on a risk-adjusted basis, it must outperform the market by a large enough amount to compensate investors for the additional risk. This often is not the case, even when the inverse fund beats the market in terms of raw unadjusted return.

Consider a hypothetical strategy that is twice as risky as the overall market, and which loses 15% in a year in which the S&P 500 gains 10%. Though the inverse of this hypothetical strategy would have made more money than the market (15% to 10%), it nevertheless would have come up short on a risk-adjusted basis. That’s because the correct benchmark against which to compare its performance is the S&P 500 bought on 2:1 leverage, which would have gained close to 20%.

The bottom line: Almost all actively managed funds and ETFs lag broad market index funds, and ETFs that do the opposite of other strategies are no exception. The best advice is to go with one of these index funds.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

Also read: ‘Love him or hate him’: New ETFs let investors bet on or against Jim Cramer and his stock picks

Plus: ETF flows point to ‘skittish’ investors as it’s ‘a little unwieldy out there’ after Fed rate hikes