New research provides perhaps the most compelling reason of all to buy and hold an index fund: Only a tiny group of stocks has provided the entire global market’s long-term gain.

If you don’t own these stocks, your net long-term gain will be no better than zero — and quite likely much worse.

The study was published recently in the Financial Analysts Journal. Entitled “Long-Term Shareholder Returns: Evidence from 64,000 Global Stocks,” the research was conducted by Hendrik Bessembinder of Arizona State University; Te-Feng Chen and K.C. John Wei of Hong Kong Polytechnic University, and Goeun Choi of Tulane University.

This group of stocks that is the source of the stock market’s long-term wealth creation is incredibly small. The researchers focused on all publicly traded stocks in the world between 1990 and 2020 — almost 64,000 in total. They found that just 1,526 securities — 2.39% of the total — accounted for all of the wealth the global equity market produced over this 30-year period. The net wealth creation of the remaining 97.61% of stocks was zero.

The return distribution was extremely lopsided even among the 2.39% of stocks that were source of the net wealth creation over this 30-year period. Just five of the more than 64,000 stocks were responsible for more than 10% of the total global wealth creation: Apple

AAPL,

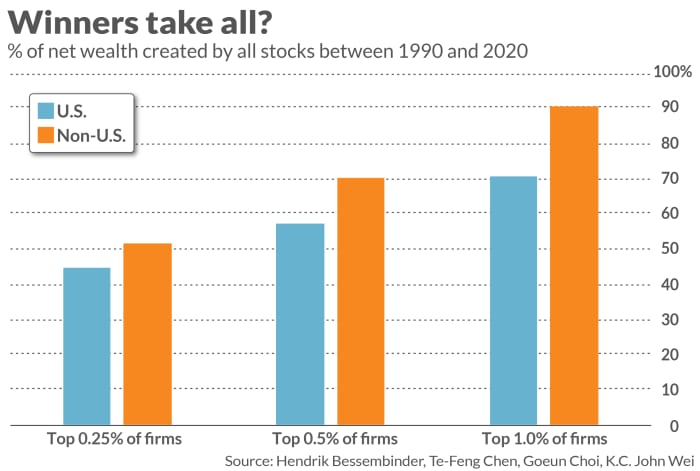

Furthermore, as you can see from the chart below, the top 0.25% of all stocks were the source of almost half of the total net wealth created over these three decades.

The extremely skewed distribution that the researchers found is a lot different than the perfect bell curve that we learn about in statistics 101. If there were that bell-curve distribution, there would be an equal chance of a given stock being above-average or below-average. In that case, stocks’ average (or mean) return would be the same as their median return (the return such that half the stocks do better and half do more poorly).

One gauge of how far stocks’ distribution diverges from a bell curve is the difference between their mean- and median return. Over the 30-year period the researchers analyzed, stocks’ mean cumulative buy-and-hold return was a gain of 366.8%. Their median buy-and-hold return, in contrast, was a loss of 6.9%.

Many on Wall Street are unaware of this skewed distribution because they extrapolate from short-term returns. But that is dangerous to do, Bessembinder said in an interview, because stocks’ skewed distribution is largely absent at short-term intervals. Stocks’ returns over a given week-, month- or even quarter largely adhere to a bell-curve distribution.

This has profound implications for financial planners, he continued. That’s because most of them base their projections of clients’ long-term returns on “mean returns and the mean of the distribution of possible future outcomes.” Yet given a severely skewed distribution, it’s not only possible but quite likely that most individual outcomes will be less than the mean.

“ If you pick a stock at random and hold it for the long term, the most likely single outcome is that you will lose almost everything. ”

Even more sobering to contemplate is stocks’ modal return — the single return that is seen more often than any other in the sample. The researchers found that stocks’ modal buy-and-hold return is an almost complete loss. Another way of putting this: If you pick a stock at random and hold it for the long term, the most likely single outcome is that you will lose almost everything.

The most obvious implication of these findings is to invest in an index fund. Unless you have the extremely rare ability to pick stocks that will be part of the tiny subset that make money over the long term, you almost certainly will lag a simple index fund.

The index fund you purchase should be benchmarked to a global stock index, furthermore. That’s because there is no assurance that U.S. stocks will be heavily represented in the tiny slice of the market that will produce all of the stock market’s future net wealth creation. It is true that, over the past 30 years, U.S. stocks did dominate that tiny subset. But this could easily be different over the next 30 years.

Just take Japan, whose stock market today is significantly lower than where it stood in 1990. Hardly any of the 2.39% of stocks that produced all of the wealth over the past 30 years are of Japanese companies. There’s no guarantee that the U.S. stock market won’t suffer the same fate in coming decades.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

More: A stock-market milestone: Apple is now worth more than the entire Russell 2000

Plus: The S&P 500 is top-heavy with tech. Here’s what that says about future stock-market returns.