You’re kidding yourself if you think you’ll know when you should reinvest the cash you have built up during the bear market of the last 18 months.

You almost certainly will wait too long, in fact. That’s why you should adopt a plan that specifies when and how you will go about returning to being fully invested.

I offer this advice not because I’m convinced a new bull market has started, though it very well may have. But I do know that you can’t base your reinvestment decision on when it “feels right.” That’s because reinvesting in stocks won’t “feel right” until the top of the next bull market bull market; that is when the news will be at its most positive extreme. We all need some plan of action to overcome the reticence we inevitably feel the rest of the time.

Fortunately, there is a wide variety of reasonable plans you could adopt, and almost any of them would be better than doing nothing. The perfect is the enemy of the good.

My inspiration in making these assertions is a classic essay Jeremy Grantham wrote in March 2009. Grantham, of course, is co-founder of Grantham, Mayo, & van Otterloo (GMO), a Boston-based asset management firm. He contended that during bear markets “those… who [are] oozing cash will not want to easily give up their brilliance.” So they will be “watching and waiting with their inertia beginning to set like concrete.” The longer they wait to develop a plan to get back in, the greater the chance that “rigor mortis sets in.”

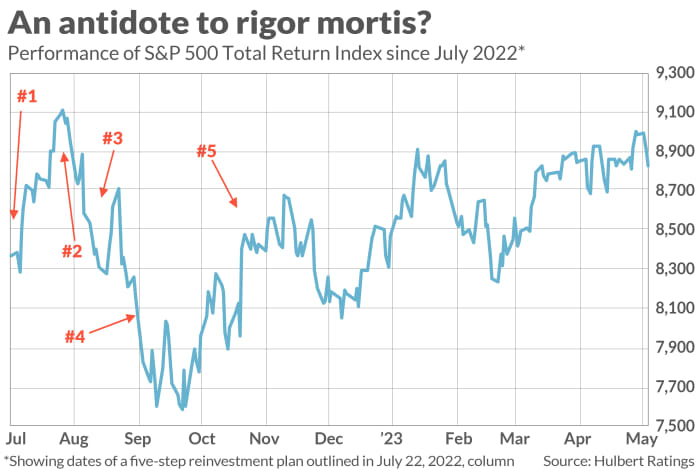

I proposed one possible such plan in a Retirement Weekly column last July, and it’s worth reviewing how that plan has worked out. I suggested then that you could “determine how much additional you would invest in the stock market to reach your desired maximum equity exposure level—and divide that additional amount into five segments. Invest one segment now, and invest each of the remaining four, in turn, whenever the stock market rises or falls 5% from where it stood when you invested the prior segment.”

The accompanying chart illustrates how this plan has worked out in practice. Those who followed the plan returned to their target weight equity exposure by November, and have retained that exposure level ever since.

There are several important takeaways:

- One is not particularly important, but worth mentioning anyway since I’m sure you’re curious: The plan made money: The lump sum that was sitting in cash last July is now 5.4% larger. But this profit is not the point. You actually would be better off over the long-term had the stock market declined by 25% or more in a straight line after last July, in which case the lump sum from last July would be sitting on a loss right now. Nevertheless, your average buy-in price would be a lot lower, which in turn would cause your long-term performance to be better.

- The more important point from a performance perspective is that last July’s plan guaranteed that the average buy-in price of the amount you reinvested would be lower than the stock market’s previous all-time high. That’s important, because most investors who get out of the market after stocks have entered a bear market wait until the market has recovered to new all-time highs before investing. By doing that, of course, they will lose ground relative to buying and holding.

- The emotional/psychological takeaway is that reinvestment plans like this one are relatively easy to actually follow. Adhering to it does not require making any anxiety-provoking all-or-nothing decisions about an entire lump sum. By instead dividing that sum into a number of tranches, you spread that anxiety out over time. And though there’s no denying that a declining market increases anxiety, you can at least somewhat lessen that anxiety by realizing that the more the market declines the better your long-term performance.

To repeat what I mentioned before, however: The particular reinvestment plan I suggested last summer is just one of many you could adopt. The important thing is to pick one and then follow it.

Waiting too long to get back in

If you have any doubt about how hard it is to get back into the market after reducing equity exposure during a bear market, consider what happened to the late Richard Russell, the famous editor of Dow Theory Letters. I credit him with making what may very well be the best market-timing call of the last 40 years.

It came in late August 1987, two months before the 1987 crash, the worst in U.S. stock market history. Russell, speaking at an investment conference I was attending, took the stage to announce that the 1982-1987 bull market had ended at its Aug. 25 closing high. At the market’s postcrash closing low, the Dow Jones Industrial Average

DJIA,

Despite thereby establishing this incredible lead over a buy-and-hold approach, Russell frittered it away over the subsequent two years. He didn’t get back into the stock market until late August 1989, two years later, when the DJIA was higher than where it stood at its 1987 peak.

My point in walking down memory lane is not to pick on Russell. My point instead is that if a market timer as accomplished as Russell failed to get back into the market in a timely fashion, what makes you think you can do better?

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com.